for an

even

more

future

future

even

more

future

future

Chamber of Commerce of Bogota

Bogotá 2012

Bogotá 2012

In 2009 Santiago Pinyol was living in Spain. Before the avalanche of anti drug campaigns that he witnessed, their evident failure, and curiously contradictory effect -the insistence on the subject simply caused more curiosity - Pinyol launched a research into what “a drug” may mean, taking into account that the subjectivity that drugs produce makes it impossible or very difficult to represent. The artist starts a operation searching for a pseudo-scientific image to transform it by representing molecules with chupa chups, the-Spanish llolipop. Thus, he comes to his work, C49H66N2O8 (2009), the molecular representation of the three most consumed drugs at that time in Spain: Cocaine, Ecstasy and THC,

building a series of fragile and colorful lollipop sculpture models representing the chemical formulas of these substances in 3D. All this in order to submit a final image, as abstract as the drug itself because, as Derrida says:

“There is no drug in nature “.

“Natural” and “naturally” deadly poisons can occur, but they are not drugs. Such as drug addiction, the drug concept represents an established, institutional definition: it needs a history, a culture, conventions, assessments, standards, a whole grid of crisscrossing speeches, a explicit or elliptical rhetoric. Later we will return around this rhetorical dimension. There is no objective, scientific, physical definition (physicalist),or “naturalist” for drugs (perhaps this definition can be considered “naturalist”, if that helps)

Pinyol flashed with strobe lights these geometric shapes, not just for the shadows to dance, but also as a reference to the history of such scientific devices, as strobe light - as important in the electronic music scene as drugs themselves - was developed to understand and perceive motion. In 2010 on his return to Colombia, Pinyol finds a newspaper article about a mix of substances used in cutting down cocaine in the street market -known as rindex- and takes that group of odorless and white substances (aspirin, gypsum, talc, etc.) as a chemical model. Again he builds fragile sculptures where each lollipop color corresponds to a chemical element (green for oxygen, red for carbon, blue for hydrogen) and each model to a chemical composition (gypsum, acetylsalicylic acid, etc). What Pinyol suggests, it is that the problem of drugs beyond the prohibitionist schemes - legal and illegal - has been poorly understood. The user reaches an unreachable experience, a test pilot for new experiences, in stark contrast to the moralizing scheme that clashes with the respect for individuality, an impossibility of representation versus subjectivity.

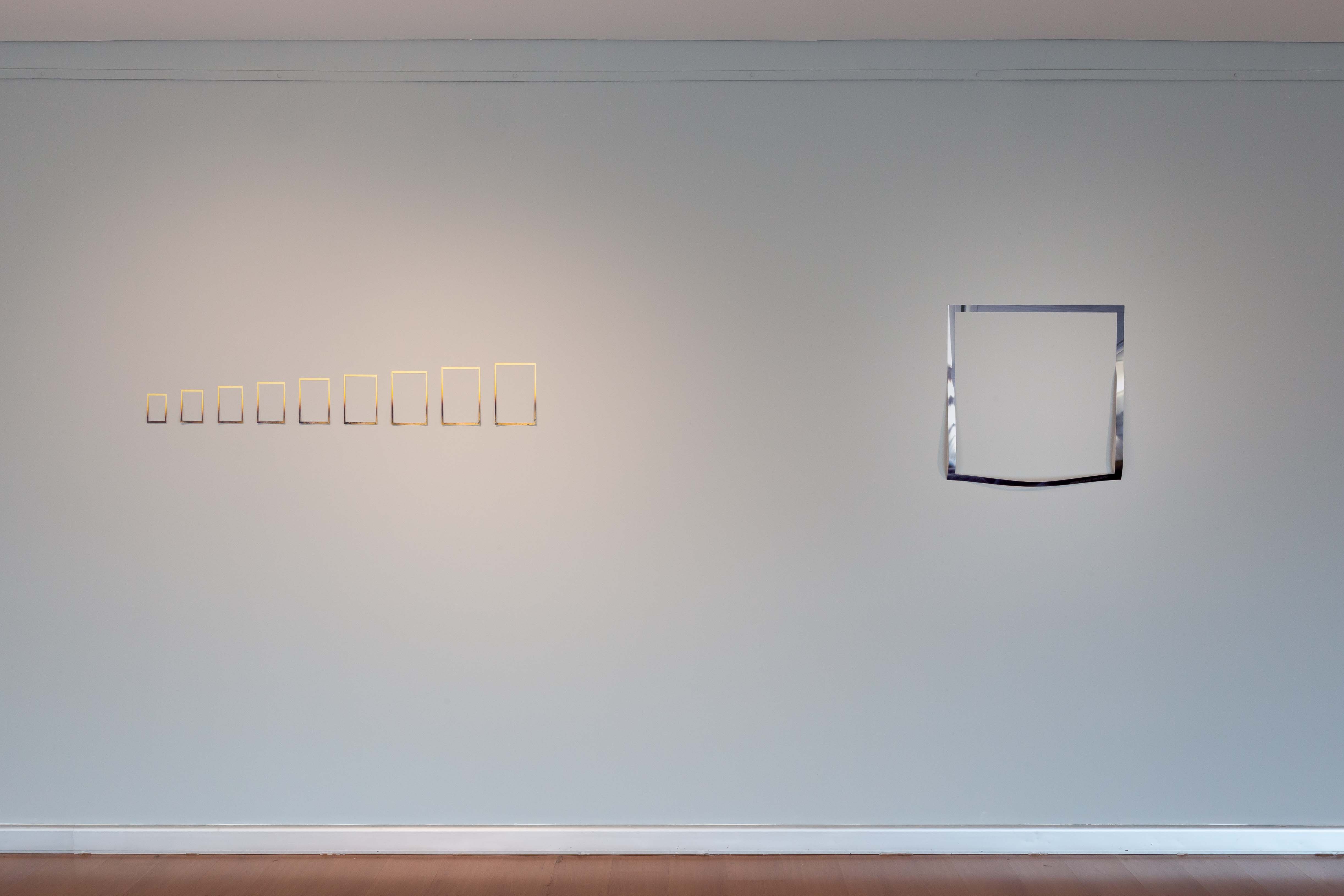

These two works constituted my initial approaches to the work of Pinyol, a work that lingers in the narrow boundary between showing and concealing. Perhaps Pinyol is an artist deeply guided, not necessarily influenced by a minimalist procedure, to a constant questioning of the real, reality, representation. There is a constant temptation towards the photographic in his work, but his three-dimensional vocation is even stronger, leading to, as we have just mentioned, making use of the material as a way to question his ideas, his sensitivity. His solo show For an even further future, fully coincides with the exhibition, also held under my curatorship in the same room at the Chamber of Commerce, One revolution per minute by Ximena Diaz. But unlike what was done by Diaz, essentially a question of a reality dominated by mass media, corporations, corruption and violence, Pinyol prefers to channel his doubts to the everyday. What do we see when we wake up? How do we look at a photograph? What do we remember? What’s behind or under what we see?

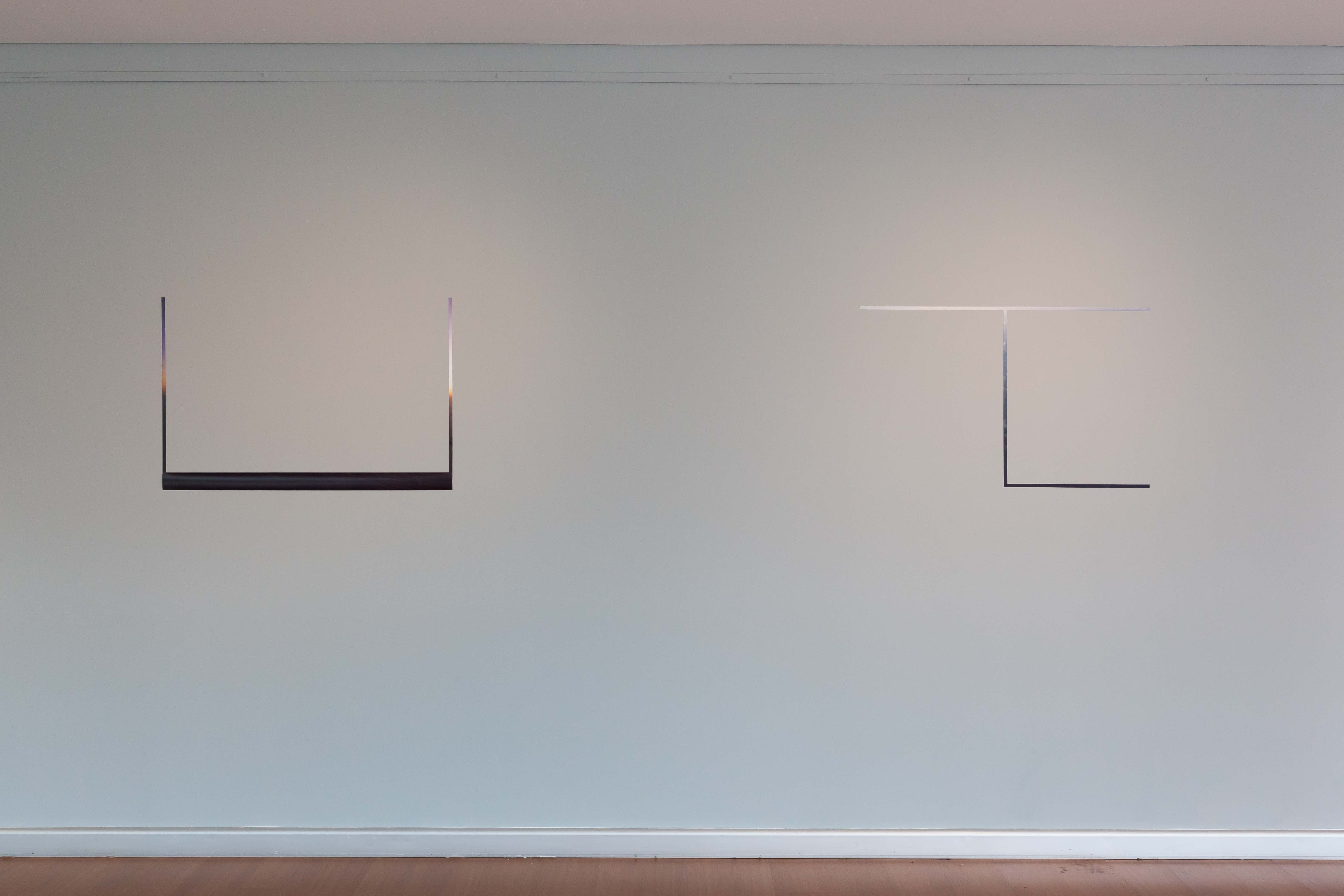

Perhaps Pinyol is interested in tracing a minor history of our modernity in this new phase of his work. Aspects of the economic production, the regulation of symbolic exchanges and subjectivity are highlighted with simple, subtle and even intimate acts, such as cutting various shapes on landscape photographs. Without letting go the idea that the artist is interested in the scrutiny and evaluation of the uses and origins of the image and what builds and constitutes a finished work of art. The formal sampling we just mentioned, the process of cutting and editing fragments, the sum of irregular and discrete units, denying the inside of a photograph to escape through its margins, crumpling pictures and placing them either on a table, or at the end of a scenic sequence fits the conceptual sampling proposed by the artist. It would seem that Pinyol tries to question about the role of the space of representation, the picture as a window or screen. In the essay The screen, Emile Zola said:

“Any work of art is like an open window towards creation; in the framing of a window there is a sort of transparent screen through which the objects are perceived more or less deformed, suffering more or less noticeable changes in their lines and their color. These changes correspond to the nature of the screen. There is no access to the exact and actual creation, but to the creation modified by the medium through which perceive the image. We see creation in a work made by a man, a temperament, his personality. The image produced on these new sort of screen of is the representation of things and people located yonder, and this picture may not be true, because every time a new screen comes between our eye and creation, it changes. Realistic display is a simple glass, so pure, so clear, that it claims to be so perfectly transparent that the images that traverse immediately reproduce in all its reality. Thus, there is no alteration, either in lines or colors: an accurate, fresh, and innocent copy. The realistic screen denies its own existence (...), it is surely difficult to characterize a screen that has as main feature the denial of its own existence. “

The perception that Zola and his contemporaries -among them Cezanne- had of the work of art “as a screen that has as main the denial of its own existence” seems to have been followed to the letter by Pinyol. But let us not forget that the artist is interested in matter, touching, crumpling, fliping the panels in which he supposedly should hang his pictures and place a blackout simulating a window. All of this in the vulnerability which supposes knowing the thinness of his tricks. Pinyol reticence and containment in this show, his critical attitude, whether to drugs or the surplus of images under the hyperconsumption tree, his resignation to the spectacular reminds the claim by Mario Merz: “Building means knowing the proportions between human being and waste of the material used by man. (...) Building is, above all, a careful examination of daily life. “ Finally, it can be said in conclusion, that the artist is interested in technologies of sight and its effects, and that for Pinyol as for Joseph Kosuth “the true works of art are the ideas.”

Santiago Rueda