gone

are

the

days

(the best way to teach art)

1 painting as living dead

There is an awkward relationship between reproduction and experience in art history and how it is taught in Latin America. It is a relation based on distance, reproductions in art books of masterpieces, works with which one never comes in contact beyond a discursive relationship, primordially textual. Curiously, we also witness a time when historical painting, and history in general, is being “revived” in an immersive experience through a “symphony of light and sound” from “a new way of experiencing art.” This fact can reveal both bureaucratic problems in the displacement of a historical work (permits, insurance, conservation, etc.) and an updating and mediation of the pictorial experience towards a contemporary, measured, calculated and, never better, spectacular phenomenology. This phenomenon can be seen represented in Van Gogh Alive, whose page can also read the following review “Gone are the days when the only way to appreciate art is by the work hanging on the wall of an art gallery … “

2 parenthesis (After “Critique and Experience” by Bernardo Ortiz)

John Baldessari’s The Best Way to Do Art reproduces a photograph of an airplane, a Boeing 747. Under the photograph a caption says: “A young artist at the arts faculty idolized Cézanne’s paintings. He looked and studied all the books he could find on Cézanne and copied all the reproductions of Cezanne he found in them. He visited a museum and for the first time saw a painting of Cézanne in real life. He hated it. It looked nothing like the Cézannes he had studied in books. From that day, he made all his paintings the size of the reproductions and painted them in black and white. He also painted the captions and the explanations that the books offered about his paintings. Many times he used only words. And then one day he realized that very few people, on the other hand, see books and magazines as he did, and also like them, they receive them by mail. The moral of this history: It is difficult to introduce a painting in a mailbox. “

(Lippard, Six Years 254)

There is an awkward relationship between reproduction and experience in art history and how it is taught in Latin America. It is a relation based on distance, reproductions in art books of masterpieces, works with which one never comes in contact beyond a discursive relationship, primordially textual. Curiously, we also witness a time when historical painting, and history in general, is being “revived” in an immersive experience through a “symphony of light and sound” from “a new way of experiencing art.” This fact can reveal both bureaucratic problems in the displacement of a historical work (permits, insurance, conservation, etc.) and an updating and mediation of the pictorial experience towards a contemporary, measured, calculated and, never better, spectacular phenomenology. This phenomenon can be seen represented in Van Gogh Alive, whose page can also read the following review “Gone are the days when the only way to appreciate art is by the work hanging on the wall of an art gallery … “

2 parenthesis (After “Critique and Experience” by Bernardo Ortiz)

John Baldessari’s The Best Way to Do Art reproduces a photograph of an airplane, a Boeing 747. Under the photograph a caption says: “A young artist at the arts faculty idolized Cézanne’s paintings. He looked and studied all the books he could find on Cézanne and copied all the reproductions of Cezanne he found in them. He visited a museum and for the first time saw a painting of Cézanne in real life. He hated it. It looked nothing like the Cézannes he had studied in books. From that day, he made all his paintings the size of the reproductions and painted them in black and white. He also painted the captions and the explanations that the books offered about his paintings. Many times he used only words. And then one day he realized that very few people, on the other hand, see books and magazines as he did, and also like them, they receive them by mail. The moral of this history: It is difficult to introduce a painting in a mailbox. “

(Lippard, Six Years 254)

3 distance and exclusion

Our relationship with art history as a discursive process can be deployed in terms of exclusion, as a distance that can not be salvaged, and at the same time as a starting point. The effects of this distance can be seen in how art education is structured in Colombia: an inherited idea of practice and academy that has little to do with our reality.

4 the best way to teach art

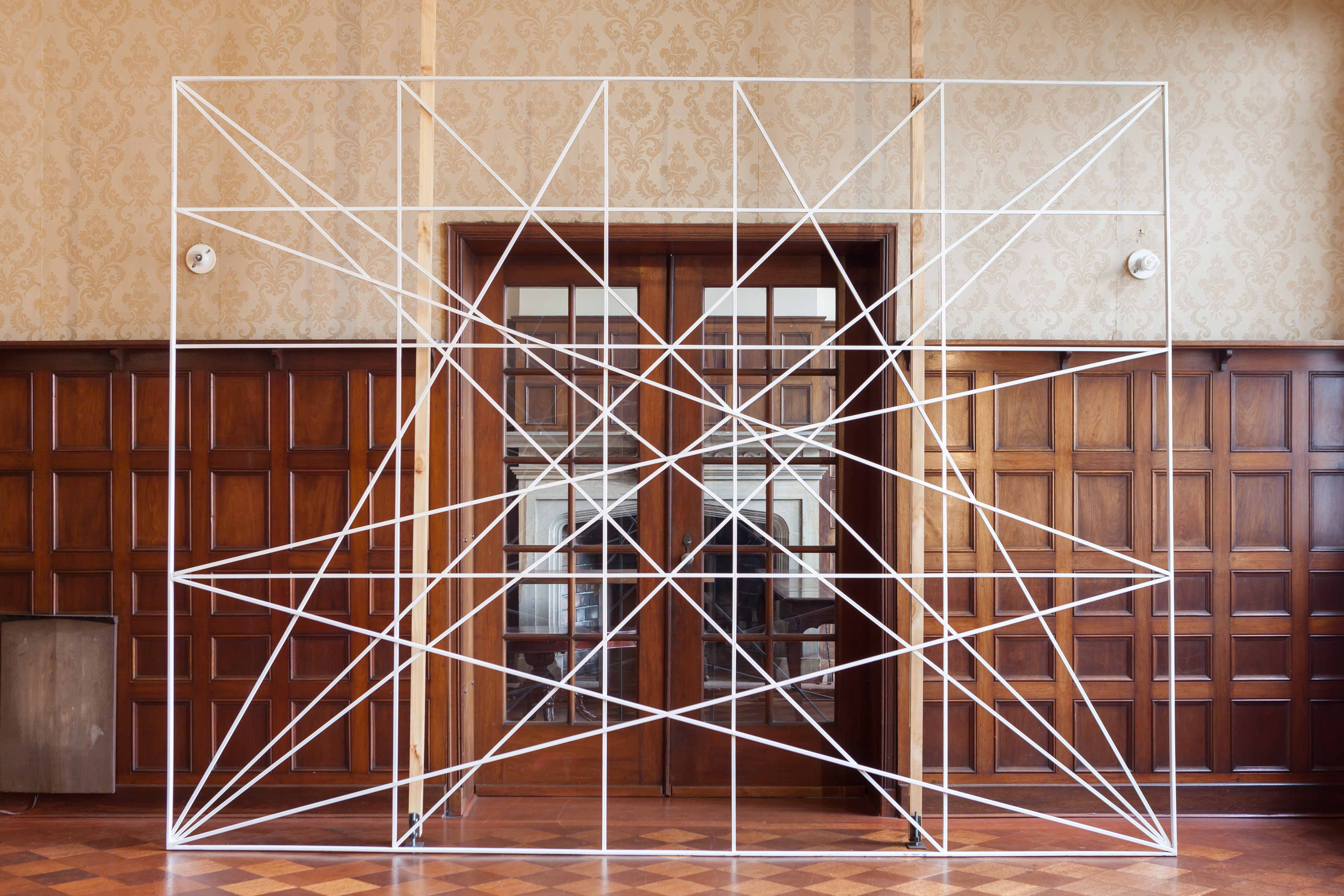

The visit of the Prado Museum to Bogota highlighted many of these points. Comprised of only 1 original painting and 53 reproductions, shown at 1:1 scale, even if this meant only showing a fragment of the whole. The visit was symbolically installed at the very center of the Plaza de Bolivar, sieging the sculpture of the Libertador. A heavy handed neocolonial didactic gesture.

In various visits I documented the site and guided tours of the exhibition as well as the work with a group of art students from El Bosque University. The visit was a performative reenactment of a scene you encounter in european museums; young art students learning by drawing copies from the masters.

Our relationship with art history as a discursive process can be deployed in terms of exclusion, as a distance that can not be salvaged, and at the same time as a starting point. The effects of this distance can be seen in how art education is structured in Colombia: an inherited idea of practice and academy that has little to do with our reality.

4 the best way to teach art

The visit of the Prado Museum to Bogota highlighted many of these points. Comprised of only 1 original painting and 53 reproductions, shown at 1:1 scale, even if this meant only showing a fragment of the whole. The visit was symbolically installed at the very center of the Plaza de Bolivar, sieging the sculpture of the Libertador. A heavy handed neocolonial didactic gesture.

In various visits I documented the site and guided tours of the exhibition as well as the work with a group of art students from El Bosque University. The visit was a performative reenactment of a scene you encounter in european museums; young art students learning by drawing copies from the masters.